Of the 5% of newborns born with a NLDO, around 90% get better on their own by the age of 12 months– the membrane occluding the duct opens spontaneously or the bone grows and the duct is no longer choked off. (For every 1,000 babies born, 50 have NLDO; by age 12 months, 5 of these 50 will still have an obstruction). The odds are heavily in favor of spontaneous resolution.

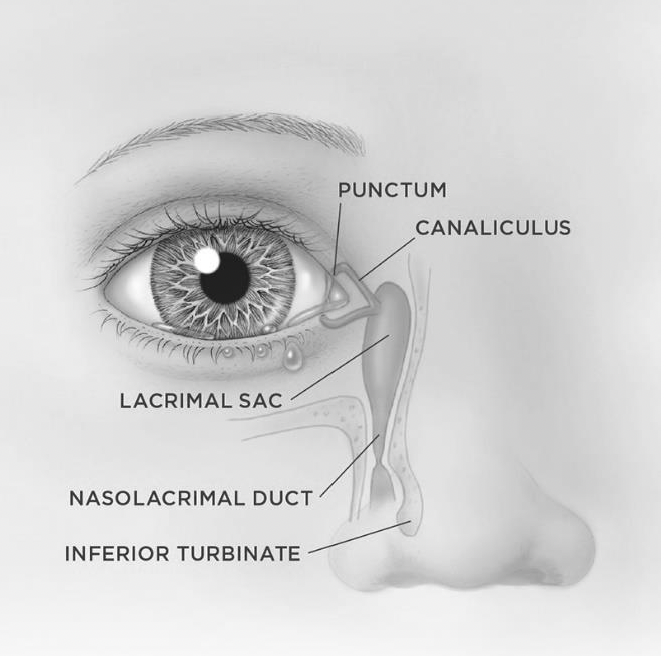

Until an NLDO spontaneously resolves, there are measures you can take to minimize the build-up of the “gooey” discharge. First and foremost, gentle massage of the lacrimal sac can be performed. This creates pushes out the mucous and debris that have built up within the obstructed tear duct system. To massage the lacrimal sac, gently press then release, the little bump at the corner of the eyelids where it meets the nose (this round spongy structures give a little and the baby will not feel any pain. Performing this massage before each diaper change will usually keep the symptoms under control. This will NOT cure the obstruction, but it will reduce the gooey discharge while you wait for the baby’s tear duct to enlarge over time.

Sometimes there is bacterial overgrowth within the blocked tear duct. Then (and only then) antibiotics can be used. As you may know, the inappropriate and indiscriminate use of antibiotics has led to the bacteria that can no longer be easily killed by antibiotics. If you need to use antibiotic eye drops, then please take care to use them as directed. For NLDO with secondary infection use one drop 2 times a day for 5 days, then try to go back to massage alone.

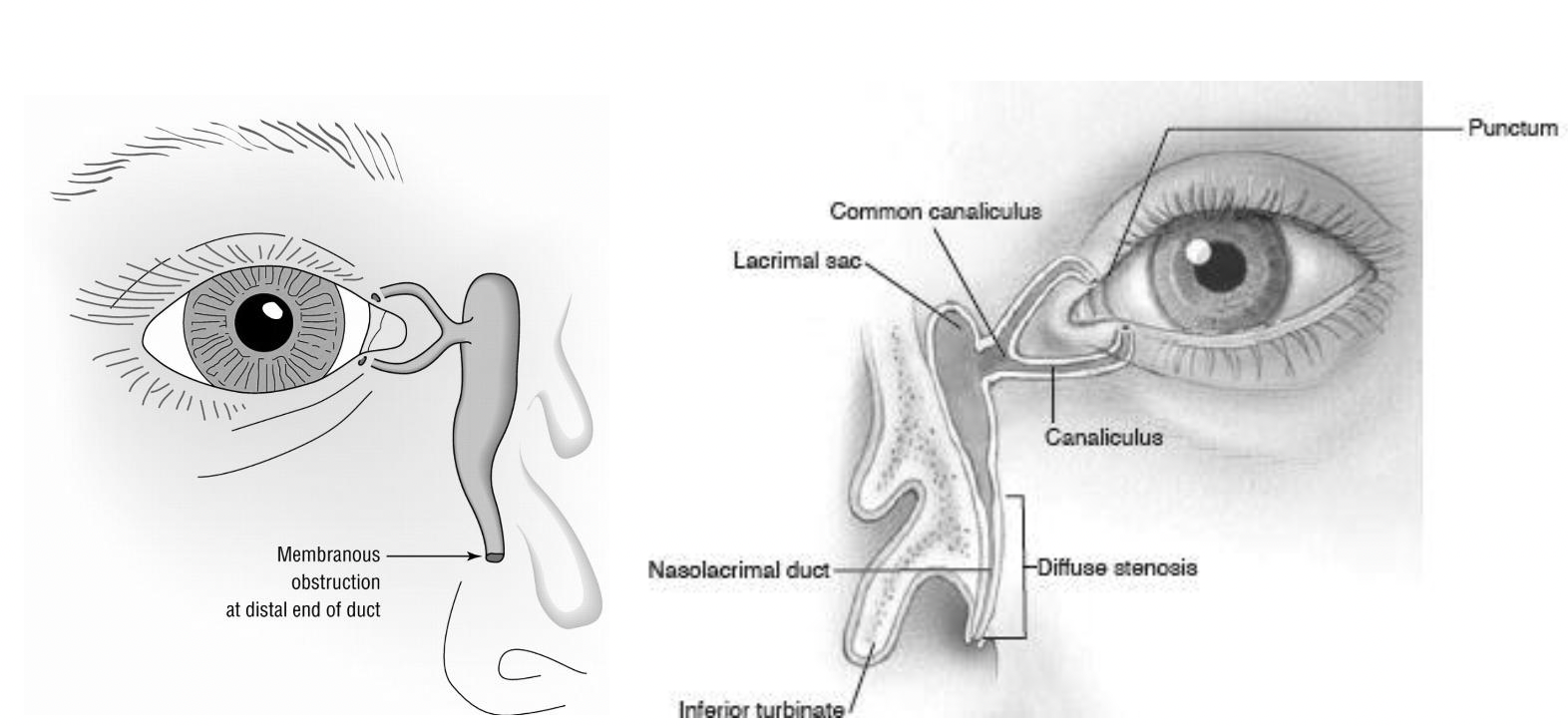

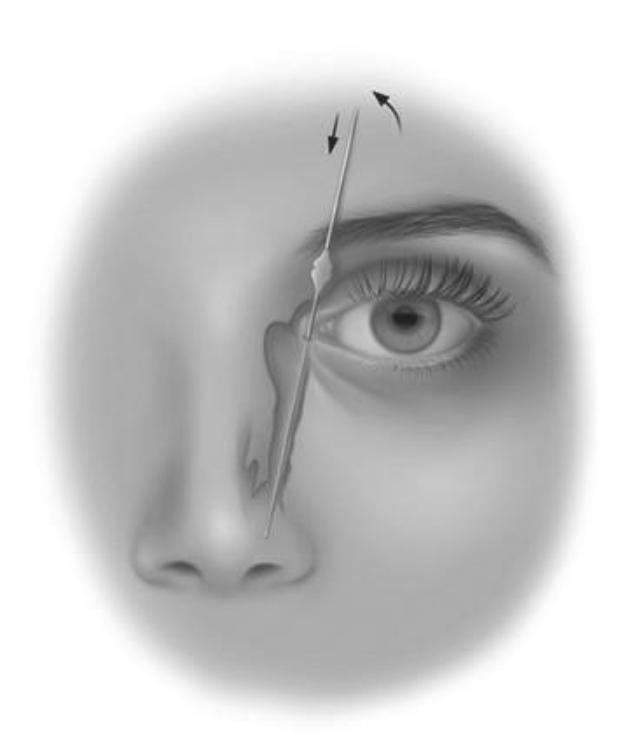

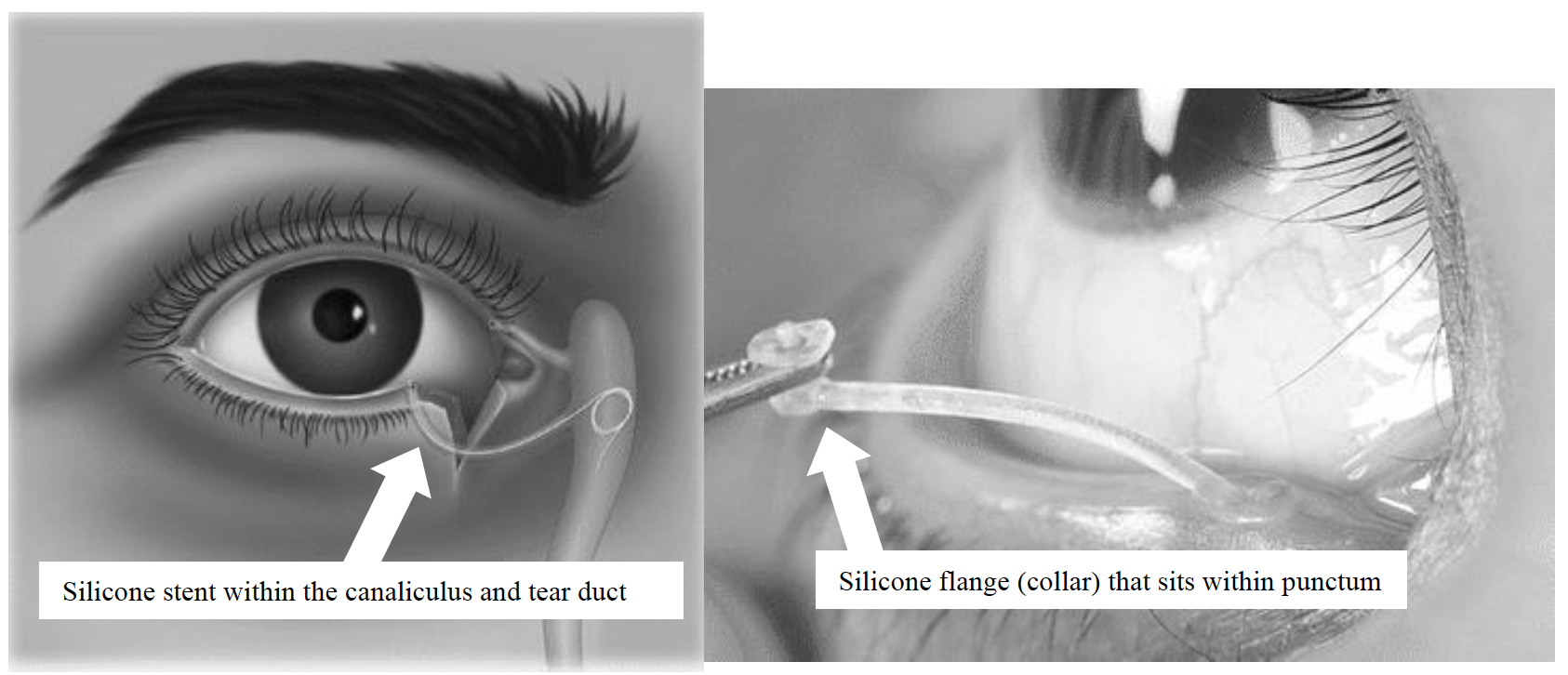

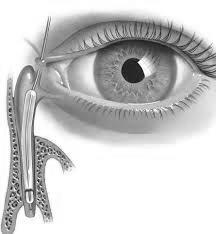

Finally, there are surgical options to open the obstruction. Inserting a metal probe into the nasolacrimal duct will open any membranes and allow the surgeon to feel whether or not the bone around the duct is too tight. This can be done safely in the office if the baby is small enough to be held relatively still; the ideal age is 6 to 9 months. The benefits of in-office NLDO probing include an excellent chance of immediate cure (95%) and the avoidance of a possible general anesthesia (see below: “What if the NLDO doesn’t go away on it’s own by the first birthday?”). Other benefits include money and time saved (fewer eye drops, less time massaging, and no need to take off from work for a trip to the operating room). The alternative is to wait for spontaneous resolution. If there is no spontaneous resolution by 13-14 months, the NLDO is unlikely to resolve on its own and a trip to the operating room is the only way to fix it. The risks of in-office probing include failure to achieve cure, infection, nosebleed, discomfort, and damage to the nasolacrimal drainage system; these same risks apply when the procedure is performed in an operating room. If, at the time of in-office probing, it becomes unsafe to proceed (baby moves too much, etc.) then the procedure is immediately stopped. Probing the nasolacrimal duct on a person who is awake is not painful, but it is by no means a pleasurable sensation. Adults with tear duct problems are routinely probed in the office and most describe it feeling like soda bubbles going up the nose.