Congenital torticollis (abnormal head position, AHP) is typically caused by a tight sternocleidomastoid muscle. These cases are evident during the first weeks of life and persist during sleep.

By contrast, acquired torticollis in infancy is often an adaptive response to an ophthalmic problem. Ocular torticollis/AHP often presents at 3 to 4 months of age. Younger infants don’t have sufficient neck strength to compensate for ocular issues. Ocular AHP typically disappears during sleep because there are no vision problems to compensate for when the eyes are closed.

Differentiating congenital from ocular torticollis is important. The consequences of inappropriate management can be profound. Specifically, initiating physical therapy for ocular torticollis will override the adaptive mechanism—the torticollis will be “treated”—but amblyopia will result as the underlying pathology remains unaltered.

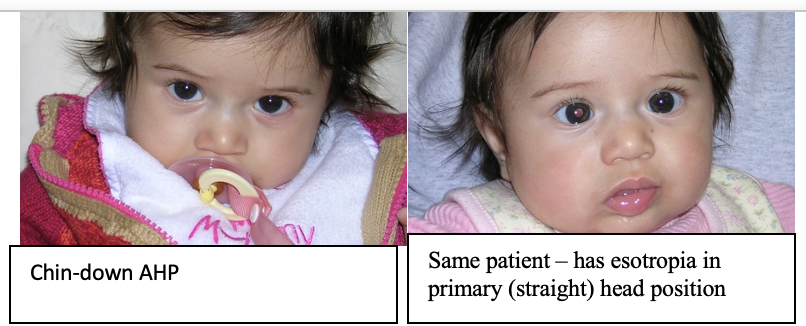

Ocular torticollis is fairly easy to identify. There are just three diagnoses in the differential: strabismus, nystagmus, and ptosis. When evaluating any infant or child with an AHP, position their head in the primary (straight) position and watch the eyes. Is there strabismus? Nystagmus? Ptosis? If there is a tilt toward one shoulder, tilt the head toward the opposite shoulder. If nystagmus, strabismus, or ptosis is present, the torticollis should be considered ocular until proven otherwise.

Why would torticollis be an adaptive mechanism? For patients with nystagmus, there is often a particular head position where the nystagmus is minimized, and visual acuity improves. With strabismus, an AHP can eliminate double vision and enhance depth perception. Finally, a chin-up head position for bilateral ptosis allows the child to use both eyes and achieve depth perception.

With this in mind, the appropriate treatment for ocular AHP is to address the underlying ophthalmic pathology. It must be stated again that overriding the adaptive mechanism of an ocular AHP through physical therapy will cause amblyopia; this vision loss can be profound and permanent.

A few categorical details are in order. A tilt describes a head tilted towards one shoulder; a turn describes face turn towards the left or right. Thus, we have head tilts and face turns. Chin-up and chin-down positions are self-explanatory. Combinations occur.

Nystagmus

Retinal cells are organized in linear arrays. When light moves across these arrays the retina is stimulated, and the light is perceived by the brain. Depending on the animal, either movement of an object or movement of the eyes will stimulate the retina. Some animals are incapable of initiating eye movements (saccades) and only see when an object moves past their eyes (or if they move their heads – think of a lion moving its head slowly side to side as it walks). In primates (yes, us!) the extraocular muscles are tonically active, causing very small movements of the eyes (micro-saccades) that effectively “paint” an image onto the retina. Saccades are characterized by the amplitude and frequency of their motion (gain = amplitude x frequency). Our retina can sense motion within a certain range of gain.

When a normal person’s eye movements are measured with electrodes, micro-saccades are detected even though the eyes appear perfectly still. Further, these micro-saccades are essentially the same wherever she directs her gaze (up, left, right…).

On the other hand, people born with an abnormal saccadic gain mechanism have infantile nystagmus. Their saccades are not “micro”, but this is an exaggeration of normal. People with infantile nystagmus have decreased visual acuity because the gain of their saccade exceeds the retina’s fixed ability to process the data.

Importantly, patients with nystagmus often have one position of gaze where the gain is minimized (dampened/nullified). By directing their eyes into this null zone the nystagmus decreases and visual acuity increases. Utilizing the null zone is a mechanism that infants quickly discover. They assume an abnormal head position (AHP) to force their gaze into a null zone. For example, a 5-month-old with a null zone in right-gaze will turn his face to the left because this forces his eyes to the right when he is looking at something directly in front of him. A 4-year-old with a null zone in up-gaze would place her chin down, forcing the eyes up. People with congenital nystagmus also have a null zone at near. When their eyes converge on a near object the gain is diminished and visual acuity improves. As a result, they usually can read much smaller print than their distance acuity would predict. Often, they can read regular type-size books and use computers without visual aids.

Eye muscle surgery can shift the null zone into the primary (straight ahead) position. By moving the extraocular muscles the null zone is shifted, mitigating (and often eliminating) the need for an AHP. These surgeries are typically delayed until 3 or 4 years of age because the character and position of the null zone may change. However, we will operate for an AHP at an earlier age if it is marked and consistent.

Another consideration is self-esteem. Adults with nystagmus report life-long feelings of inadequacy and shame from “looking different” and their inability to maintain normal social eye contact. In our experience, verbal children and adults are uniformly pleased by the outcome of nystagmus surgery. In addition to minimization/elimination of the AHP, the amplitude is usually diminished to the extent their nystagmus becomes less obvious.

Finally, most patients report an improvement in their visual acuity with these surgeries. While eye-chart (subjective) acuity is not typically improved, the time required for visual recognition is improved because the gain is decreased.

Ptosis

In congenital ptosis the muscle-tendon complex that elevates the eyelid (levator aponeurosis) is abnormal with an excess of elastic tissue and a paucity of muscle. This manifests as poor lid elevation, lid lag (when looking down, the lid stays up) and poor formation of the upper lid crease.

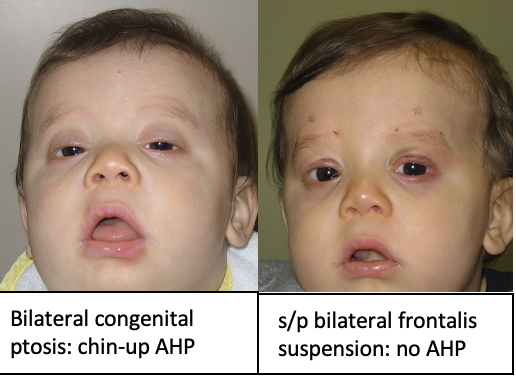

In cases of marked bilateral ptosis, patients lift their head to see; otherwise, the lids block both pupils. When these infants have their head placed in the primary (straight) position the ptosis covers both pupils. Congenital ptosis does not “go away” and there is no advantage to surgical delay when it is causing an AHP. It is difficult to walk when the chin is up in the air and musculoskeletal changes to the face and neck can result from delayed treatment. Our preference is to operate at the earliest, safest date after diagnosis.

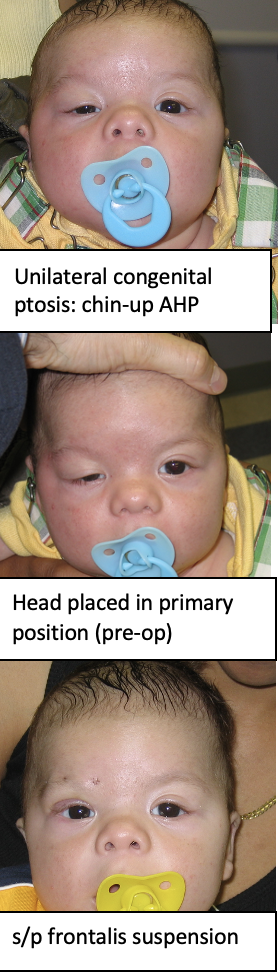

Unilateral ptosis can also cause an AHP. As primates we have excellent depth perception and an innate drive to see in three dimensions. Infants with unilateral ptosis may raise their chin, allowing them to use both eyes and see things in stereo. Ironically, a chin-up AHP from unilateral ptosis is a favorable finding as it demonstrates that the child has not developed amblyopia and his depth perception is normal. Much more problematic is the child with marked unilateral ptosis and no AHP as they probably have amblyopia. Marked unilateral ptosis in an infant needs to be corrected as soon as possible and there is no clinical advantage in delay.

If a ptosis is not severe enough to cause amblyopia or an AHP then it is reasonable to wait until a child is 4 or 5 years old before surgical repair. Children younger than this don’t typically notice their appearance and are unlikely to be teased, but it is acceptable to do surgery at younger ages if the family is highly motivated.

There are two methods for repairing ptosis: tightening the levator muscle or mechanically lifting the lid. To operate on the levator, an incision is usually made through the eyelid skin; in certain cases the incision can be made on the undersurface of the lid. Mechanically lifting the eyelid (sling) involves placing material deep to the skin to suspend and hold the lid in place. Many different suspension materials are available and all fail sometimes.

The most common problem associated with pediatric ptosis surgery is the need for reoperation. It is impossible to predict who will need more than one surgery or the interval between surgeries. A more serious postoperative concern is corneal dryness from the (desired) initial overcorrection; this is more of an issue with suspension procedures. It is essential to keep the eye lubricated during sleep for the first month or so since the lid will not close properly. Also, lid lag becomes more pronounced particularly when a suspension procedure is performed.

While the primary goal of ptosis repair is functional – to eliminate an AHP, treat amblyopia and restore binocularity – we aim for excellent cosmesis. Perfect cosmesis is hard to achieve in pediatric ptosis as what looks good on the OR table can look different once the patient is vertical and running around.

Strabismus

With strabismus the eyes are pointing in different directions. This disrupts fusion and causes diplopia. When a strabismus measures the same amount, regardless of gaze, then it is comitant. However, when a strabismus varies with gaze, then it is incomitant. People with incomitant strabismus often have a position of gaze where the eyes are straight. When they direct their eyes in that direction diplopia is eliminated and depth perception restored. Given our innate preference to avoid diplopia and enjoy depth perception, people with incomitant strabismus often assume an AHP.

The most common types of incomitant strabismus are superior oblique palsy, Duane syndrome and A- or V-patterns.

Superior Oblique Laxity (“Palsy”)

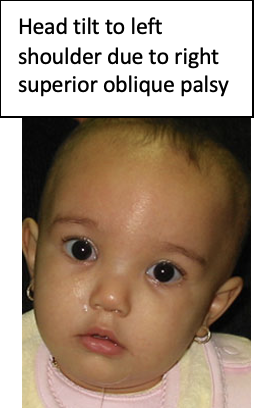

The most common form of strabismic AHP is superior oblique “palsy.” The word “palsy” is in quotes because the deficit is mechanical, not neurologic. These children have a loose superior oblique tendon, reducing the power of that muscle and allowing its antagonist (inferior oblique) to dominate. The inferior oblique’s job is to rotate the eye up and out. Therefore, an eye with superior oblique palsy is dominated by the inferior oblique and the eye is rotated up and out. This is demonstrated when the patient looks horizontally: the eye pointing towards the nose (adduction) shoots upwards. To compensate for the inferior oblique overaction these patients tilt their head towards the opposite shoulder. A child with a right superior oblique palsy tilts her head towards the left shoulder.

Superior oblique palsy often presents in infancy with a head tilt. Unfortunately, some of these cases are mistaken for congenital torticollis and physical therapy initiated.

When diagnosed in an infant, it is best to correct a superior oblique palsy sooner rather than later to avoid mid-facial hemi-hypoplasia and neck deformity. Torticollis of any etiology can result in mid-facial hemi-hypoplasia: the side of the face closer to the ground or further from the midline develops anomalously. Superior oblique palsy is well treated surgically; most cases are effectively resolved with one surgery.

In older children and adults, most cases of superior oblique “palsy” have been present since childhood but become more pronounced with time. These patients often complain of eyestrain or “headache” and may not realize that they are tilting their head, but old photographs often depict a head tilt since infancy.

Duane Syndrome

This type of strabismus is caused by aberrant connections between the abducens (6th) and oculomotor (3rd) nerves. Duane Syndrome is found in isolation in two-thirds of cases but about one-third of these patients have associated findings involving the cervical and/or thoracic spine and/or hearing deficits. It is our practice to recommend a hearing evaluation for all children diagnosed with Duane Syndrome.

Duane Syndrome is characterized by an inability to rotate the eye(s) properly, resulting in an incomitant strabismus. To avoid diplopia (and maintain depth perception), these patients assume an AHP. While the AHP is present from early in life many parents do not notice it until the child starts to walk.

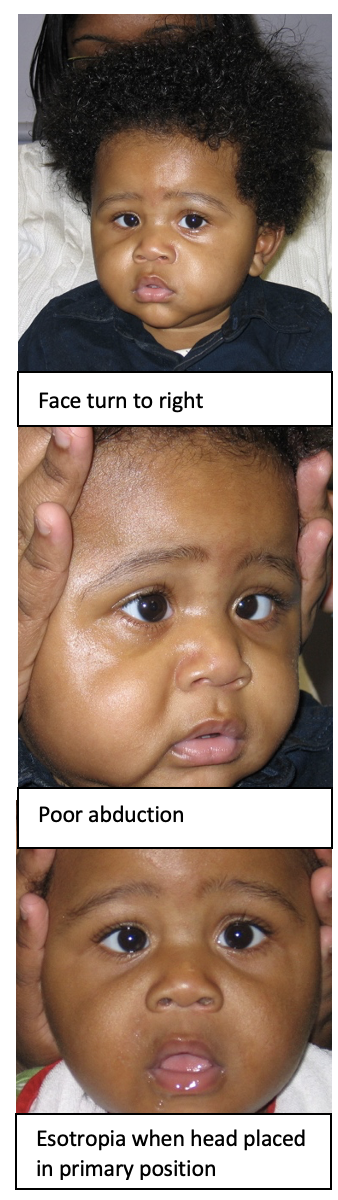

Duane Type 1 is the most common presentation (70%). The affected eye does not abduct properly (move towards the ear) and turns inwards (eso-deviation) in primary position. Esotropia disappears when the patient looks away from the affected side. For example, a boy with Duane 1 of the right eye has an esotropia most pronounced when looking towards the right but the esotropia will disappear when he looks to the left. Because his esotropia goes away in left gaze, he will turn his face to the right and look towards the left. If you straighten his head, you will see the esotropia. A key finding distinguishing Duane Syndrome from a 6th nerve palsy is that the space between the eyelids will change with ocular rotation in Duane Syndrome. When the affected eye is in abduction (towards the ear) the lids get further apart; in adduction (towards the nose) this lids come closer together.

Duane Type 2 is characterized by deficient adduction (towards the nose). As a consequence, these patients manifest an incomitant exotropia. Duane Type 3 is when both adduction and abduction are abnormal. The eyes are typically straight when looking straight ahead, but to avoid double vision these people must to turn their face because one of the eyes does not move properly. Type 3 Duane is rare. All forms of Duane Syndrome can be bilateral as well as unilateral. There may also be “up-shoots” and/or “down-shoots” of the affected eye in side-gaze.

The treatment of Duane Syndrome is surgical. There is no benefit in prolonged surgical delay when an AHP is already present; nobody outgrows Duane Syndrome. More than one surgery may be warranted but this goes for all forms of strabismus. As each patient has their own unique “dose” of rotational abnormality and AHP surgical planning varies with the individual. However, there is one overarching goal: to provide a straight head with straight eyes.

A and V Pattern Strabismus

Most patients with an eso- or exo-tropia have a comitant deviation (it’s the same magnitude in all directions of gaze). However, some have a vertically incomitant deviation: the strabismus is larger in up or down gaze. For example, an infant might have an esotropia that becomes larger when looking down but straight eyes when looking up; this is a V-pattern because the eyes follow the shape of the letter “V.” These patients compensate by finding an AHP allowing them to use both eyes.

For a V-pattern esotropia, this means looking up (by placing the chin down). In a V-pattern exotropia, the strabismus is smallest in down-gaze, so the patient will want to look down assume a chin-up AHP.

Strabismus surgery is highly effective in treating pattern strabismus.